|

From EdWeek: The Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) is one of the two assessment consortia charged with designing the Common Core assessments in Math and Literacy, and the governing board of the PARCC recently voted to provide a Spanish version of the math test to states that have voiced a need. Surprisingly, Massachusetts asked to have such a test for high school. Not surprisingly, Arizona is not interested, even though both these PARCC member states share the same ludicrous and English-only law governing the education of English learning students.

2 Comments

Interesting new study in press at the Journal of Public Economics used regression discontinuity to address how Texas elementary school students performed when separated by districts that implemented Spanish-English bilingual education programs that those that didn't. In Texas, if a district enrolls 20 or more students from a common language background (in this case, Spanish), then that district is required to provide bilingual education. Less than 20, no bilingual education, but rather English-as-a-second-language (ESL). The researchers looked at districts that enrolled between 8 and 39 students from Spanish-speaking backgrounds. They looked at student performance on state test indicators and found, generally, that kids who attend schools in bilingual education districts did significantly better on achievement outcomes than kids enrolled in ESL districts. However, those significant differences were driven by the performance of the kids who did not receive language services, that is, the English proficient students! There were no significant differences between the native Spanish speakers enrolled in bilingual or ESL districts.

The findings are interesting, but the real takeaway appears to be that keeping LEP kids away from EP kids is likely beneficial to the EP kids but a wash for the LEP children. This was one of the arguments used by pro-bilingual education forces in Colorado when a measure proposing the elimination of bilingual education was on the ballot in 2002 (see Escamilla, Shannon, Carlos, & García, 2003). EdWeek reports that the Smarter Balanced consortium, one of the two national consortia charged with creating the tests that will be aligned with the Common Core standards, recently announced the nature of the supports that will be allowed during their assessments. The announcement included accommodations for both students with disabilities and English learners. The tests have three categories of digital features: "universal tools, which are available to all students; designated supports, which are available to students at a teacher’s or school team’s discretion; and documented accommodations, which are supports that are a part of a student’s individualized education plan or other disability support plan". Perhaps most interesting (to me, at least) is the inclusion of limited translation options, as a designated support, for the math portion of the assessment. This includes the provision of word-to-word translation as well as full item translation.

Currently the full array will be available in Spanish with a more limited set of options in Vietnamese and Arabic. The point is also made that these supports are "designated" because some states may have laws that preclude any type of instruction or assessment in a language other than English (read: AZ and MA), though supporters note that, with increasing standardization of how ELs are assessed (via the WIDA) there may be a rigorous basis for comparing whether these supports aid performance for students in states that use them and states that don't. Here is the release from the consortium itself. The ever bilingual-friendly Huffington Post recently reported on a new study in Frontiers of Psychology by a student of Judith Kroll, who is a noted figure in bilingualism and cognition. The HuffPost titles the piece, "Bilinguals Have Higher Level Of Mental Flexibility, Research Shows", clearly quoting a press release issued to psychcentral.com in which the reporter states that "Penn State researchers discovered that as bilingual speakers learn to switch languages seamlessly, they develop a higher level of mental flexibility" (emphasis added). However, the study itself (conducted with balanced Spanish-English bilingual adults) essentially indexed the response time of accurately reading cognates or non-cognates that were highlighted in a Spanish or English sentence. Cognates were read with faster response times than non-cognates, suggesting that bilinguals have both their languages active even when reading monolingually. However, nowhere in the study is there a comparison to, say, a monolingual control group that would allow one to conclude that bilinguals possess a "higher level" of mental flexibility. Rather, the results confirm existing notions of a common conceptual store of information that is equally accessible irrespective of language, and that bilinguals are linguistically unique language users.

I like positive press for bilingualism and its benefits, but sometimes it seems like ideology has us drawing conclusions that range outside the data. This is classic. One of the two Common Core test development consortia, Smarter Balanced, has launched a new webpage "meant for parents, students, and teachers, and includes information about the new tests and how they will be made accessible to all students, including English-language learners", reports Lesli Maxwell at EdWeek. I thought there was a type-o, and that a new webSITE had been launched. But no. Visit the page, called "Smarter en Español". Indeed the splash page is in Spanish, but click on anything else in the menu bars across the top and you immediately revert to English. A laudable effort, but it underscores lack of support for languages other than English in the new federal educational frameworks.

EDWeek has a story about determining how to label kids in states that have adopted the World-Class Instructional Design and Assessment (WIDA) English language proficiency standards and its associated assessments. Without a common assessment system with guidelines for identification and reclassification, proponents state, it is impossible to know how states serve their emergent bilingual, English-learning, populations.

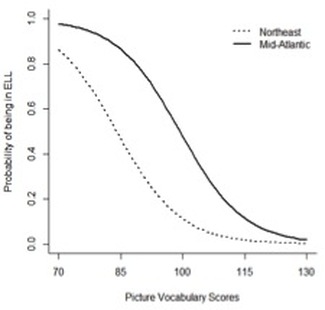

Work I have conducted with my University of Maryland colleagues, Rebecca Silverman and Jeff Harring, provides some evidence for the initial claim that state-to-state (probably district-to-district and even school-to-school) identification patterns are erratic. We took language and reading data on 161 Spanish-speaking Latino children, 1/3rd from a district in Massachusetts and 2/3rds from a district in Maryland. There were no differences between kids in MA and MD on our measures of English word reading or vocabulary, but in MA only 38% of the kids were labeled as ELL while in MD 74% of the students. This nifty odd-ratio graph shows the differential probability of being labeled ELL for kids who share similar English vocabulary profiles. A score of 100 on the x-axis is equal to 50th percentile performance and the likelihood of being labeled ELL is on the y-axis. In the MA district (Northeast), an average performing student has less than a 20% chance of getting an ELL label, while that same kid in MD (Mid-Atlantic) has about a 60% chance. The two districts are close to one another only at the tails of the distribution of vocabulary scores. So the MA district is likely withholding services to students while the MD district is likely over-servicing kids. One thing the EDWeek article doesn't discuss at all is the type of services that kids receive once they've been identified. That seems sort of important too. Scott Dual-Language Elementary Magnet School, in Topeka, Kansas is just the second school in the state to implement a 2-way immersion program, the Topeka Capital-Journal reports. The economic argument for bilingualism takes front and center, with no mention of language rights for kids of any language background, or about what might actually be best for children learning English as an additional language. So, the article is a little like so many others, but still, bilingual programs continue to make some traction in US educational circles.

|

Archives

March 2021

Categories |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed