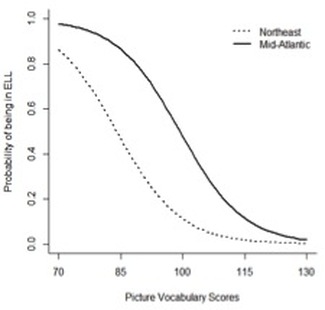

Work I have conducted with my University of Maryland colleagues, Rebecca Silverman and Jeff Harring, provides some evidence for the initial claim that state-to-state (probably district-to-district and even school-to-school) identification patterns are erratic. We took language and reading data on 161 Spanish-speaking Latino children, 1/3rd from a district in Massachusetts and 2/3rds from a district in Maryland. There were no differences between kids in MA and MD on our measures of English word reading or vocabulary, but in MA only 38% of the kids were labeled as ELL while in MD 74% of the students. This nifty odd-ratio graph shows the differential probability of being labeled ELL for kids who share similar English vocabulary profiles. A score of 100 on the x-axis is equal to 50th percentile performance and the likelihood of being labeled ELL is on the y-axis. In the MA district (Northeast), an average performing student has less than a 20% chance of getting an ELL label, while that same kid in MD (Mid-Atlantic) has about a 60% chance. The two districts are close to one another only at the tails of the distribution of vocabulary scores. So the MA district is likely withholding services to students while the MD district is likely over-servicing kids. One thing the EDWeek article doesn't discuss at all is the type of services that kids receive once they've been identified.

That seems sort of important too.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed